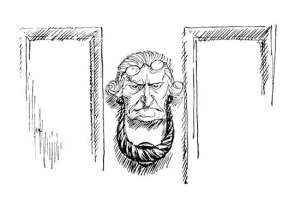

Scrooge fell upon his knees, and clasped his hands before his face.

“Mercy!” he said. “Dreadful apparition, why do you trouble me?”

“Man of the worldly mind!” replied the Ghost, “do you believe in me or not?”

“I do,” said Scrooge. “I must. But why do spirits walk the earth, and why do they come to me?”

“It is required of every man,” the Ghost returned, “that the spirit within him should walk abroad among his fellowmen, and travel far and wide; and if that spirit goes not forth in life, it is condemned to do so after death. It is doomed to wander through the world—oh, woe is me!—and witness what it cannot share, but might have shared on earth, and turned to happiness!”

Again the spectre raised a cry, and shook its chain and wrung its shadowy hands.

“You are fettered,” said Scrooge, trembling. “Tell me why?”

“I wear the chain I forged in life,” replied the Ghost. “I made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it. Is its pattern strange to you?”

Scrooge trembled more and more.

“Or would you know,” pursued the Ghost, “the weight and length of the strong coil you bear yourself? It was full as heavy and as long as this, seven Christmas Eves ago. You have laboured on it, since. It is a ponderous chain!”

Scrooge glanced about him on the floor, in the expectation of finding himself surrounded by some fifty or sixty fathoms of iron cable: but he could see nothing.

“Jacob,” he said, imploringly. “Old Jacob Marley, tell me more. Speak comfort to me, Jacob!”

“I have none to give,” the Ghost replied. “It comes from other regions, Ebenezer Scrooge, and is conveyed by other ministers, to other kinds of men. Nor can I tell you what I would. A very little more is all permitted to me. I cannot rest, I cannot stay, I cannot linger anywhere. My spirit never walked beyond our counting-house—mark me!—in life my spirit never roved beyond the narrow limits of our money-changing hole; and weary journeys lie before me!”

It was a habit with Scrooge, whenever he became thoughtful, to put his hands in his breeches pockets. Pondering on what the Ghost had said, he did so now, but without lifting up his eyes, or getting off his knees.

“You must have been very slow about it, Jacob,” Scrooge observed, in a business-like manner, though with humility and deference.

“Slow!” the Ghost repeated.

“Seven years dead,” mused Scrooge. “And travelling all the time!”

“The whole time,” said the Ghost. “No rest, no peace. Incessant torture of remorse.”

“You travel fast?” said Scrooge.

“On the wings of the wind,” replied the Ghost.

“You might have got over a great quantity of ground in seven years,” said Scrooge.

The Ghost, on hearing this, set up another cry, and clanked its chain so hideously in the dead silence of the night, that the Ward would have been justified in indicting it for a nuisance.

“Oh! captive, bound, and double-ironed,” cried the phantom, “not to know, that ages of incessant labour by immortal creatures, for this earth must pass into eternity before the good of which it is susceptible is all developed. Not to know that any Christian spirit working kindly in its little sphere, whatever it may be, will find its mortal life too short for its vast means of usefulness. Not to know that no space of regret can make amends for one life’s opportunity misused! Yet such was I! Oh! such was I!”

“But you were always a good man of business, Jacob,” faltered Scrooge, who now began to apply this to himself.

“Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

It held up its chain at arm’s length, as if that were the cause of all its unavailing grief, and flung it heavily upon the ground again.

“At this time of the rolling year,” the spectre said, “I suffer most. Why did I walk through crowds of fellow-beings with my eyes turned down, and never raise them to that blessed Star which led the Wise Men to a poor abode! Were there no poor homes to which its light would have conducted me!”

–From Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol